By MATTHEW HOLT

If health policy wonks believe anything it’s that primary care is a good thing. In theory we should all have strong relationships with our primary care doctors. They should navigate us around the health system and be arriving on our doorsteps like Marcus Welby MD when needed. Wonks like me believe that if you introduce such a relationship patients will receive preventative care, will get on the right meds and take them, will avoid the emergency room, and have fewer hospital admissions—as well as costing a whole lot less. That’s in large the theory behind HMOs and their latter-day descendants, value-based care and ACOs

Of course there are decent examples of primary care-based systems like the UK NHS or even Kaiser Permanente or the Alaskan Artic Slope Native Health Association. But for most Americans that is fantasy land. Instead, we have a system where primary care is the ugly stepchild. It’s being slowly throttled and picked apart. Even the wealth of Walmart couldn’t make it work.

There are at least 3 types of primary care that have emerged over recent decades. And none of them are really successful in making that “primary care as the lynchpin of population health” idea work.

The first is the primary care doctor purchased by and/or working for the big system. The point of these practices is to make sure that referrals for the expensive stuff go into the correct hospital system. For a long time those primary care doctors have been losing their employers money—Bob Kocher said $150-250k a year per doctor in the late 2000s. So why are they kept around by the bigger systems? Because the patients that they do admit to the hospital are insanely profitable. Consider this NC system which ended up suing the big hospital system Atrium because they only wanted the referrals. As you might expect the “cost saving” benefits of primary care are tough to find among those systems. (If you have time watch Eric Bricker’s video on Atrium & Troyon/Mecklenberg)

The second is urgent care. Urgent care has replaced primary care in much of America. The number of urgent care centers doubled in the last decade or so. While it has taken some pressure off emergency rooms, Urgent care has replaced primary care because it’s convenient and you can easily get appointments. But it’s not doing population health and care management. And often the urgent care centers are owned either by hospital systems that are using them to generate referrals, or private equity pirates that are trying to boost costs not control them.

Thirdly telehealth, especially attached to pharmacies, has enabled lots of people to get access to medications in a cheaper and more convenient fashion. Of course, this isn’t really complete primary care but HIMS & HERS and their many, many competitors are enabling access to common antibiotics for UTIs, contraceptive pills, and also mental health medications, as well as those boner and baldness pills.

That’s not to say that there haven’t been attempts to build new types of primary care

Oak Street, ChenMed and Iora (now part of One Medical) were built with the idea of bumping up the primary care services given to seniors in Medicare Advantage, with the idea that–like Kaiser and its competitors–they can take financial risk for specialty and hospital care. The theory, as Iora’s founder Rushika Fernandopulle always said, was “double the spending on primary care and reduce overall costs by 30%.” It’s not too clear if they ever got there.

Of course like everything else in American health care Oak Street and Iora were repeats of earlier efforts by Mullikin, Friendly Hills, HealthPartners and many more to manage overall care costs by taking primary care capitated risk. None of these experiments were left alone by the finance bros long enough to see what would have happened if they played out. The stock market of the 1990s and the 2020s are full of graveyards of publicly traded primary care groups that all had very promising starts. Had they been left alone long enough to grow organically it’s possible that we would see a different future. We might even see that future if Included Health, Transcarent and others manage to build out their primary care/telehealth/navigation/Centers of Excellence offering. But it’s going to take a while

Overall, risk-bearing primary care remains a lonely business despite it being the preferred policy wonk solution since Sydney Garfield started taking prepayment from workers on the Grand Coulee Dam in 1933

Of course this being America you can still get excellent primary care, it is just going to cost ya.

Silicon Valley multi-millionaires pay Jordan Shlain’s Private Medical $40k a year plus for white glove service. At the other end of the scale, One Medical collects $80-200 a year from patients paying for access to next day appointments, NPs who actually answer emails and a free telehealth service for urgent care. In between is a whole host of doctors who have opted out of the hassle of billing insurers and are charging between $500 and $5000 a year for concierge care. Then there are a ton of primary care based services using telehealth, home visits and NPs, often combined with onsite clinics at workplaces

Which means that the number of those providing genuine Marcus Welby MD style primary care in the community continues to fall.

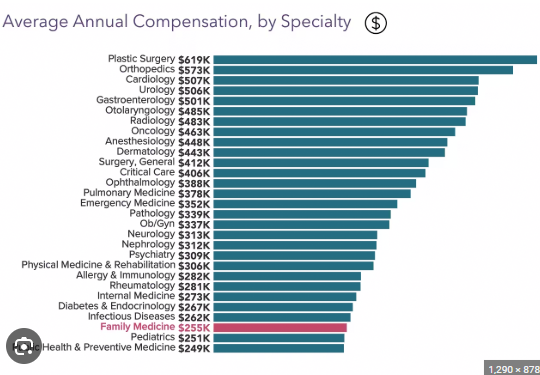

And it’s not too hard to figure out why. The average primary doctor makes a whole lot less than their specialty counterparts.

The fees for primary care are low. They’re set that way deliberately by the RUC (the Relative value scale update committee) which is dominated by specialists and essentially sets Medicare fees, which are then followed by most private insurers. So most doctors tend to look at the top end of this chart rather than the bottom they are choosing their residency slots. American health care is expensive because we have too many specialists doing marginally useful care, and too many hospitals (and pharma and device companies) making bank off them. And it’s all related to that chart.

There was a rather odd count by KFF saying that nearly 50% of American doctors were in primary care, but that counted a whole lot of doctors are “primary care” who don’t deliver traditional primary care. This is of course wrong but it gives a hint for the solution.

There are 340 million Americans. We can give everyone a PCP and put them in a panel of 600 people (as opposed to the 2-3,000 typical PCP panel. That number happens to be what MDVIP and other concierge services offer. That would require 570 thousand PCPs. Which is about 60% of doctors post-residency in America.

So if we converted all those currently licensed PCPs and added NPs, we could give EVERYONE in America concierge style care. Those doctors would be immediately available and help their patients navigate the system.

Its proponents believe that concierge medicine is not only better but also tends to be much cheaper than regular care. MDVIP claims that it saves $2500 per patient even after paying its doctors more, which is about 20% of health spending. My contention is that we could give each PCP $2k per patient (or $1.2m per 600 patient panel), of which they could use (my guess) $300-500k to run their practice, and they could keep $700K to pay themselves.

So my proposal is we give everyone really high-end primary care, pay primary care docs really well and save a boatload of money. And apparently we have nearly enough primary care docs to do it. For sure if they were paid $700K a year we’d soon find plenty more of them.

Matthew Holt is the Publisher of THCB