VIRGIL CARTER WAS more than a casual observer as he sat in his Apple Valley, California, living room Jan. 28 to watch the NFC Championship Game. In fact, it might be said the 78-year-old former quarterback played a key role, especially when it came to two controversial plays.

When Detroit Lions coach Dan Campbell ignored convention on a pair of fourth-down calls in the second half, failing to convert deep in San Francisco 49ers’ territory, critics blamed Campbell’s adherence to analytics as one of the reasons for the Lions’ 34-31 loss.

Carter’s response: “Don’t blame me.”

It might seem strange that someone who played in the NFL for seven seasons — with modest success — would need to deflect blame 48 years after retiring, but Carter is more than a former quarterback.

He is considered one of the founders of modern NFL analytics. And while analytics help coaches make the most informed decisions, they don’t guarantee success. ESPN Analytics slightly favored Campbell’s decisions, but the executions fell short, so don’t blame Carter.

In 1971, Carter and Northwestern professor Robert Machol published a three-page paper called “Operations Research on Football.” The study included two important concepts — different yard lines and situations on the field carried different expected point values, and teams should be more aggressive in certain fourth-down situations.

It took a few decades, but Carter and Machol’s findings have made a big impact. The point-value model, which is now known as expected points added (EPA), is used by coaches at all levels to evaluate offensive effectiveness. All NFL teams have at least one analytics staffer, and college programs are using third-party consulting firms to evaluate aspects such as which cornerback is most likely to get beat on a given passing play.

And yes, more teams are keeping the offense on the field on fourth downs.

“A lot of what’s in that paper is literally the same thing that’s being done now,” said Michael Lopez, the NFL’s senior director of football data and analytics. “The numbers have changed because football’s evolved, but just the idea that that existed so far before people got onto it, I think it’s pretty neat.”

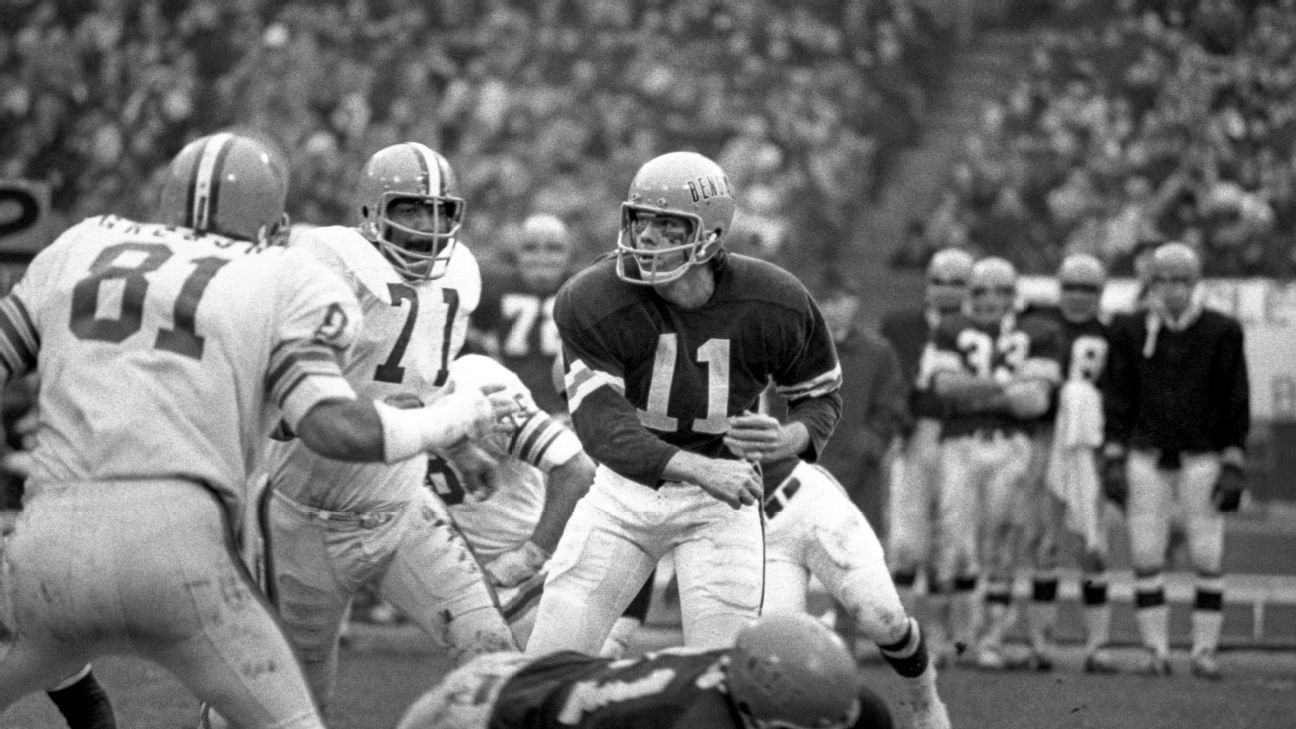

CARTER WAS SELECTED in the sixth round of the 1967 draft by the Chicago Bears, but he was not a typical rookie.

While most players live close to the team’s practice facility in Lake Forest, Carter lived in downtown Chicago. After majoring in statistics on an academic scholarship at BYU, Carter wanted to pursue an MBA at Northwestern, which offered those courses at its downtown campus, along Lake Michigan.

Bears owner George Halas, who was in his last year as head coach, not only encouraged it but, Carter said, gave him a stipend for room and board so the quarterback could stay in the city yet also be available to watch tape and learn the playbook.

Machol turned out to be the perfect professor for Carter’s study of qualitative analysis. Machol was a Harvard grad who served as a Navy lieutenant commander in World War II. He took his Northwestern students to Cubs games on field trips to study how decisions affected outcomes and win probabilities.

And as much as Machol enjoyed applying his work to sports, Carter enjoyed working with numbers.

“I’ve just always been infatuated with being able to work to a conclusion of value, and it was either right or wrong,” Carter told ESPN.

They came up with the idea to measure the value of ball placement on a football field. In their work, Carter and Machol noted that no major studies had been done aside from a letter to the editor to a research quarterly, written by Charles Mottley in 1954.

To do this, Carter needed play-by-play information. With Halas’ blessing, Carter reached out to the PR office for each NFL team and received data from every team except the Oakland Raiders. Carter filled in the gap with information from their opponent and charted 56 games during the first half of the 1969 season.

The biggest finding was about “having an approximate knowledge of the value of having the ball at a particular point on a field,” they wrote in their paper. That impacted everything from play selection near the goal line to the concept of the “coffin corner” punt that places the ball as deep as possible into opponent territory without kicking the ball into the end zone.

An example can be drawn from the NFC Championship Game. San Francisco had 0.9 expected points when it had a first-and-10 on its own 25-yard line. Later in that drive, the expected points jumped up to 3.0 for a first-and-10 at Detroit’s 34-yard line, according to ESPN’s EPA model.

The ideas and notions were considered radical at the time. And for decades, they went unnoticed.

Said Brian Burke, a senior analytics specialist at ESPN: “It was literally way, way ahead of its time.”

BY THE TIME the report was published, Carter was no longer in Chicago. He was waived after the 1969 season and ended up with the Buffalo Bills for a brief period. The Bills traded him to the Cincinnati Bengals in exchange for a sixth-round pick before the 1970 season began. That’s when Carter’s work gained more traction. Not only was Paul Brown, the Bengals’ head coach and team founder, interested, but the quarterbacks coach also took notice. His name was Bill Walsh.

Long before Walsh won Super Bowls with the San Francisco 49ers, he was developing the origins of his fabled West Coast offense with Carter in Cincinnati. For example, they worked through the risk assessment of throwing an out route near the goal line and decided it was safer to throw the ball near the pylon instead of trying to hit a receiver in stride. Carter also explained to Walsh why the chances of scoring a touchdown are better if a receiver gains a first down at the 15-yard line instead of the 10.

“He thought, ‘Well, that’s interesting,'” Carter said. “But then he’s [also] thinking, ‘Well, how can I explain that to Paul Brown? Because if we don’t score, I’ll be the guy in the hot seat.'”

They also worked on a concept that is standard for modern quarterbacks — reading a defense and getting the ball out quickly. When Walsh took over as 49ers coach in 1979, Carter, then retired, took his son to training camp and was immediately greeted by quarterback Joe Montana.

The first thing Montana told him was that he used to get “damn tired of looking at you make a five-step drop and throw to Bob Trumpy in a curl over the middle” in game film as Walsh installed the West Coast in San Francisco.

After going largely undeveloped, EPA, along with other current concepts, such as the building blocks for items such as rush yards over expectation and Total QBR, were either reintroduced or expanded in the 1988 book, “The Hidden Game of Football,” by Bob Carroll, Pete Palmer and John Thorn.

Those works referenced a fundamental principle — not all yards are gained equally.

For example, in Week 16 of last season, Green Bay Packers quarterback Jordan Love had an 8-yard completion to gain a first down on third-and-7 and netted the Packers an EPA of 2.1. However, in the 21 instances that a team gained 8 yards on third-and-9 and was short of a first down, 19 of those plays resulted in a negative EPA. But each play was still considered an 8-yard gain in the final box score.

It wasn’t until 2008, when Burke formally introduced EPA, that these concepts began to gain momentum. A fighter pilot by trade who worked as a defense contractor with American allies, Burke crunched the numbers on long international flights. He borrowed a log-in for the NFL’s play-by-play data and eventually built an expected points model for all four downs.

Eventually, the analytics shifted from information on websites on the fringes of the sport to being embraced and used by every NFL franchise.

“Now it’s everywhere,” Burke said. “It’s kind of like watching your kids kind of grow up and have their own lives, move out, get married and have their own kids.”

IF IT WAS ever considered a revolution, the numbers show the war is over.

There’s a 33% increase in teams going for it on fourth-and-1, according to Lopez. He also added that the majority of teams have an analytics staffer communicating real-time probabilities during games via the coaching headsets.

The increase in analytics usage, Burke said, could be chalked up to outlets such as his original website — AdvancedFootballAnalytics.com — that showed the inefficiencies in previous metrics. Fans and teams also were exposed to articles and leaderboards that showed which players were more efficient. It also became much easier for those interested in analytics to access data and statistical models.

Some of the most successful teams over recent years, such as the 49ers, Baltimore Ravens, Philadelphia Eagles and Bills, have been among the teams that most use analytics.

Sam Francis is the Bengals’ football data analyst and leads the team’s analytics. His office is on the same floor as those of the coaches at the team facility, and since he started working in the NFL in 2017, he has seen how the advanced numbers have become more prevalent.

“The more conversations we have, the more projects we do, the more studies we do, they’re going to understand what I have access to and how it can be used,” Francis said.

When he started out, stats such as EPA were buried on the right side of spreadsheet reports. Now, EPA has moved farther left as more people value it. When the Bengals evaluated rushing offense this offseason, EPA was the first column as they ranked teams across the league by run concept. Veteran offensive line coach Frank Pollack, a no-nonsense ex-NFL lineman, was the one explaining the numbers to the rest of the staff.

The process in Cincinnati and elsewhere around the league shows the importance of integrating the analytics department with coaches, especially now that accurate speed and tracking data is readily available.

“[The] best organizations at this point, your analysts are fully integrated with your coaches or your scouts,” Lopez said. “You’re going to overhear stuff that you wouldn’t have thought of. Then you overhear it and you’re like, ‘Holy cow, we can measure that. We can check that.'”

The same can be said at the college level. Championship Analytics patented a game book in 2016 that coaches hold on the sideline to gauge whether to go for it on fourth down.

“Some people in the past have been stubborn — ‘Hey, we’re going to run this play because I’ve been running it for the last 20 years, or whatever it is,'” said Baylor offensive coordinator Jake Spavital, whose grandfather coached Virgil Carter for a season in the World Football League. “And then you’re looking at it and you’re just not getting the results as these other plays are, so why should we be running these plays that often?”

THE MORE TECHNOLOGY advances, the more football and the numbers that shape the game will evolve.

One of the big questions, Burke said, is how artificial intelligence will be used to help interpret all of the advanced player tracking data that comes from microchips in the football and in players’ shoulder pads. But, as with all data, understanding it requires understanding how the game is played, too.

“I had to learn the game at a deeper level,” Burke said. “And now coaches sort of have to learn a little bit about analytics, and we’re meeting in a happy middle.”

Carter and Machol unknowingly modeled that dynamic more than 50 years ago. The synergy and trust that produced their groundbreaking paper is just as critical now as it was then.

“It’s not their job to trust me,” Francis said. “I’ve got to earn that. I’ve got to gain that. Because at the end of the day, there’s only so many decisions that a coach makes, and they’re going to impact how he’s viewed with his job and his career.”

Part of the evolution of analytics is how much easier it has become to gather and deliver the data.

When Carter set out on his project in 1970, the entire process took more than 160 hours. Burke refined and modernized EPA during the summer of 2008. Now, Francis can tweak reports the day after a game in as little as 15 minutes.

But although the processing time has shortened, the objective has remained the same since those days back at Northwestern.

“EPA, from a general understanding across the league now, has probably only been — to be generous — the last 10 years,” Francis said. “[Carter] was trying to uncover this stuff 50 years ago.”